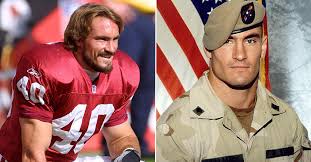

To Hardtke it was quintessential Tillman, doing everything that was asked of him and then doing even more.“I don’t look at that as defying what I said,” Hardtke said. “I look at it as his approach to the way he lived his life and the way he played the game.”His legacy lives on in the Pat Tillman Foundation, which has sent 871 Tillman Scholars to graduate school at a cost of more than $34 million.Tillman first starred in baseball. In the book, “Where Men Win Glory: The Odyssey of Pat Tillman,” author Jon Krakauer cited a 2002 entry from Tillman’s diary about how the sport boosted his self-esteem.“As odd as this sounds, a diving catch I made in the 11-12 all-stars was a take-off point,” Tillman wrote. “I excelled the rest of the tournament and gained incredible confidence. It sounds tacky but it was big.”

An undersized 13-year-old freshman at Leland, Tillman had muscular forearms and calves, according to Hill, and was extremely athletic. However, Tillman gave up baseball when told he couldn’t make varsity. Hardtke, the football coach, told him he was making a mistake.“He said, ‘Coach, I’m going to get in the weight room, I’m going to get big and strong and play Division I football,’” Hardtke said. “I told him, ‘Pat, you have a better chance at baseball than you do at football.’ See how smart I was as a coach?”After a career that included a Pac-12 Defensive Player of the Year award and ASU’s second-ever Rose Bowl berth, Tillman faced the same skepticism about his ability in the NFL Draft as he did coming out of Leland. He lasted until the seventh round before being taken by the Arizona Cardinals.Tillman became a standout safety, playing from 1998 through 2001. His decision to enlist in the Army and join the Rangers elite fighting force along with his brother Kevin after the 9/11 attacks surprised friends and family, although they weren’t shocked.

Leave a Reply