NEW YORK (AP) — Bud Harrelson, the sketchy and sure-gave shortstop who battled Pete Rose on the field during a season finisher game and assisted the New York Mets with coming out on top for a surprising title, passed on early Thursday morning. He was 79.

The Mets said Thursday that Harrelson passed on at a hospice house in East Northport, New York after a long fight with Alzheimer’s. He was analyzed in 2016 and freely shared his battle two years after the fact, trusting he and his family could help other people tormented.

All through his wellbeing trial, Harrelson remained associated with his expert unrivaled delight. He was part-proprietor of the Long Island Ducks, an autonomous small time group found minutes from his home. He called his times of work with the club — which he was instrumental in beginning and running — his most prominent accomplishment in baseball.

The group said Harrelson’s family was arranging a festival of his life for a later date.

During a significant association vocation that endured from 1965-80, the light-hitting Harrelson was chosen to two Elite player Games and dominated a Gold Glove. Referred to family and partners as Pal, he enjoyed his initial 13 seasons with New York and was the main man in a Mets uniform for both their Worldwide championship titles.

RELATED Inclusion

Picture

Reds’ Ashcraft wins 5-minute deadlock with Yankees even before Cincinnati finishes 3-game range

Picture

Nationals clear Mets

Picture

Hamilton, O’Neill drive in runs in the twelfth inning to lift Red Sox over Marlins 6-5

The first came as the infield anchor of the 1969 Supernatural occurrence Mets, the other as the club’s third base mentor in 1986.

In perhaps of the most popular scene in baseball history, it was an euphoric Harrelson who waved home Beam Knight with the triumphant sudden spike in demand for Bill Buckner’s mistake in Game 6 of the ’86 Series against Boston.

Harrelson likewise dealt with the Mets for almost two seasons, directing them to a second-place NL East completion in 1990 in the wake of taking over in late May. He was drafted into the group’s Lobby of Acclaim in 1986, joining Corroded Staub as the initial two players regarded.

“It was not difficult to see the reason why the ’69 people adored him. He was perfect on safeguard and he was extreme,” Mets telecaster Ron Sweetheart, who pitched for the club from 1983-91, told the New York Post in 2018.

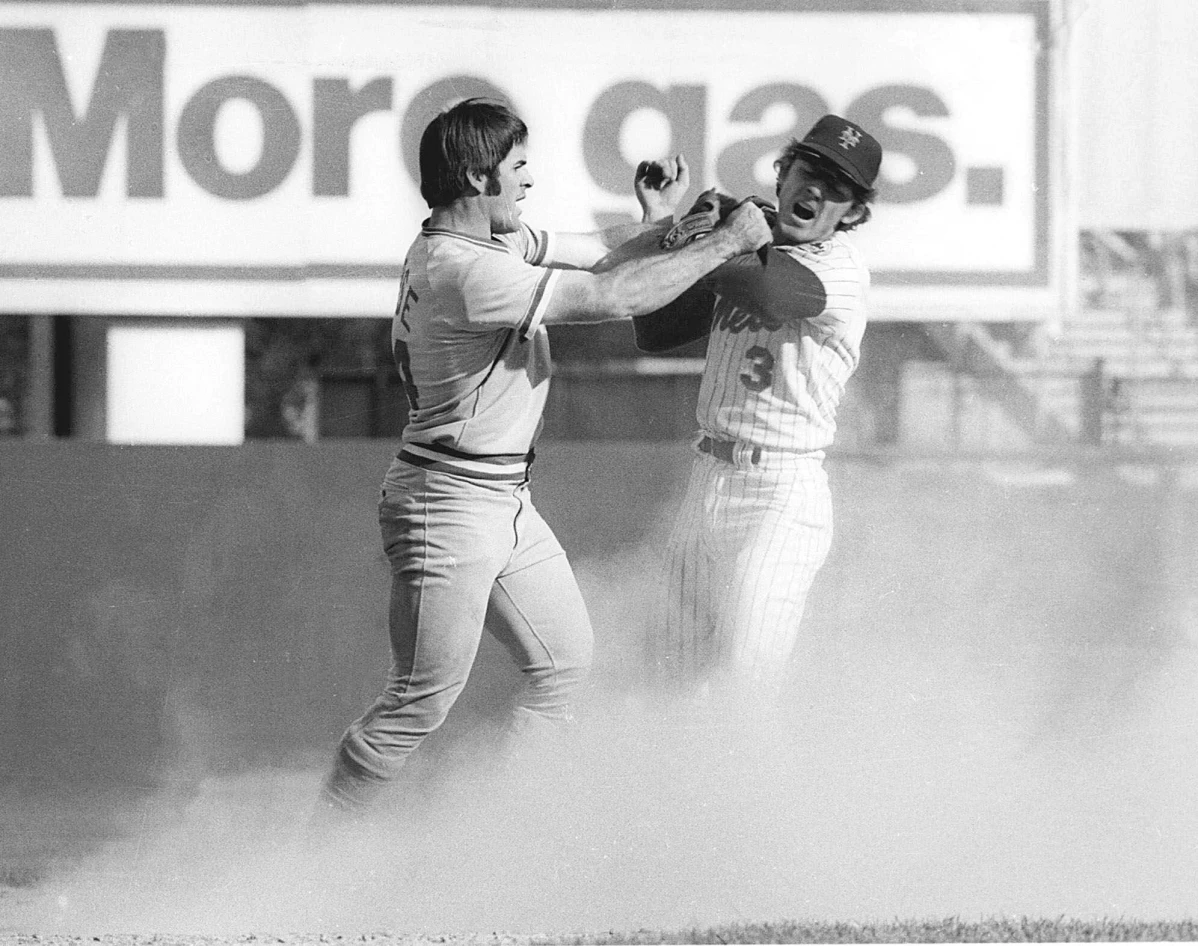

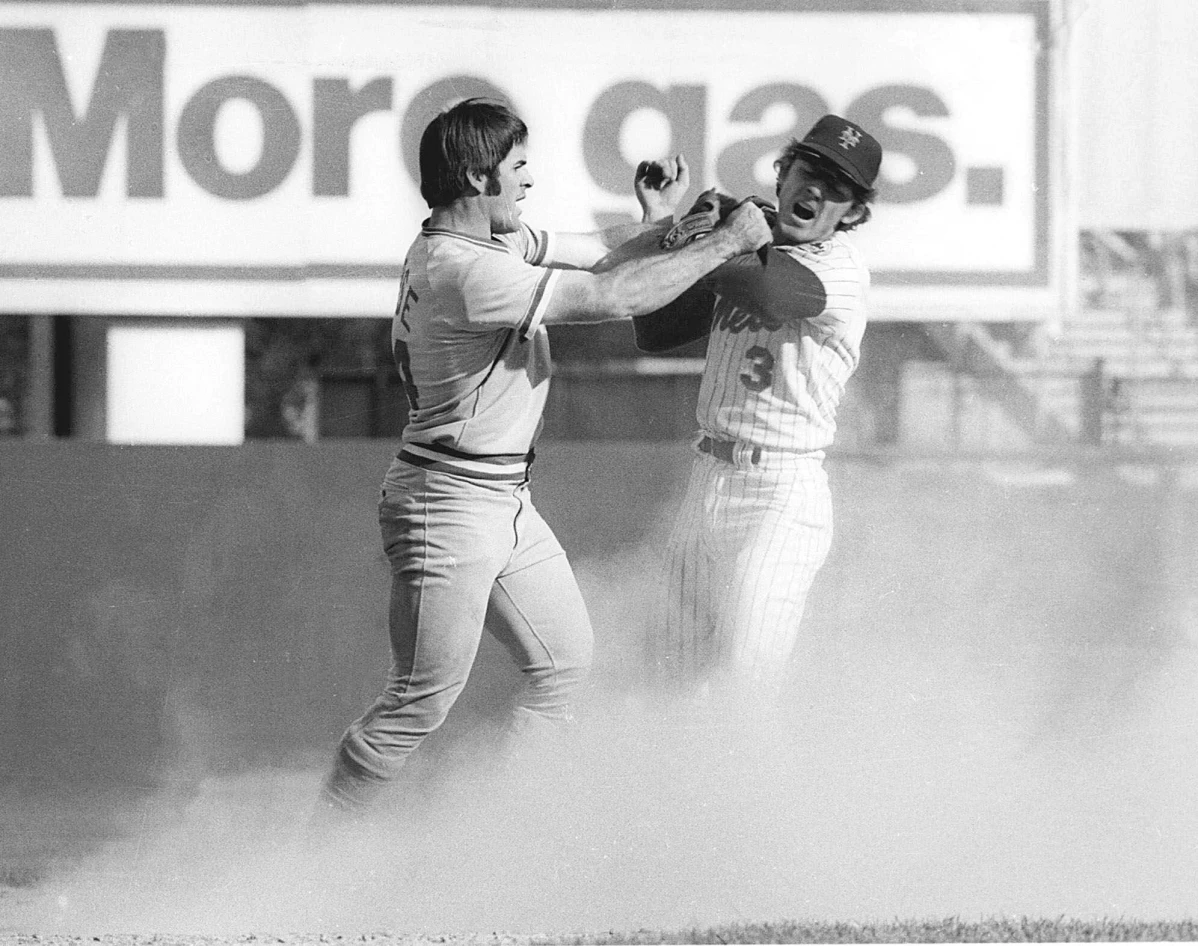

In Game 3 of the 1973 NL Title Series between the Mets and Cincinnati Reds, Rose slid hard into Harrelson at a respectable halfway point on a twofold play. The two wound up head to head and afterward wrestling in the infield soil at Shea Arena, setting off a wild, seat clearing fight that spilled into the outfield.

Offset by in excess of 30 pounds, the super skinny, coarse Harrelson got the most terrible of it.

However, he didn’t withdraw.

“I regret absolutely nothing about grinding away with Rose. I did how I needed to safeguard myself, and Pete did how he assumed he needed to attempt to persuade his group,” Harrelson wrote in his 2012 diary, “Turning Two: My Excursion to the Highest point of the World and Back with the New York Mets” co-created by Phil Pepe. “We battled and that was its finish.”

Kind of.

The game was held up as incensed fans flung objects at Rose, and the Reds were pulled off the field by administrator Sparky Anderson until request was reestablished. Mets captain Yogi Berra and players including Willie Mays and Tom Seaver went out to passed on field to quiet the group.

Cincinnati players obviously were irritated about a remark from Harrelson after Game 2. Downplaying his own weaknesses, Harrelson said Mets pitcher Jon Matlack “made the Large Red Machine seem as though me hitting” after the left-hander threw a two-hit shutout.

“I didn’t think it was all that awful. I was somewhat putting myself down a tad, however I was likewise putting them down,” Harrelson said. “Then, at that point, I heard that they planned to come after me what not, so I figured that was all there was to it not too far off. Furthermore, when Pete hit me after I’d previously tossed the ball, I blew up. Also, we had the little match. He only sort of lifted me up, laid me down to rest and it was everywhere.”

Harrelson later composed that Charlie Hustle got him with “a shameful move.” Yet the previous shortstop would likewise kid about the fracas, frequently saying: “I hit him with my best punch. I hit him directly in the clench hand with my eye.”

The two became partners in Philadelphia years after the fact and while their playing days were long finished, Harrelson said Rose, baseball’s vocation hits pioneer, marked a photograph of the battle for himself and stated, “Gratitude for putting me on the map.”

Harrelson later dealt with Rose’s child with the Ducks, and the senior Rose even gone to two or three games, Harrelson said.

Harrelson was exchanged to the Phillies 1978 and enjoyed two years with them prior to playing his last season for the Texas Officers. A switch-hitter, he completed his vocation with a .236 batting normal and .616 Operations. He hit seven homers — never more than one in a season — and took 127 bases, remembering a vocation high 28 for the Mets for 1971.

In spite of his absence of force, Harrelson could be annoying at the plate. He attracted 95 strolls 1970 and was consistently a decent bunter. He batted .333 lifetime (20 for 60) against Lobby of Famer Bounce Gibson, with 14 strolls and only three strikeouts for a .459 on-base rate.

“I have consistently said I’ll take God to three-and-two and take my risks. I could foul two off before He gave me ball four,” Harrelson composed.

Harrelson fell off the seat in the 1970 Top pick Game in Cincinnati, getting two hits and scoring two times. He was the Public Association’s beginning shortstop the accompanying season at Tiger Arena and won his main Gold Glove that year.

“He was the best shortstop who played behind me – period,” previous Mets pitcher Jerry Koosman said in an explanation delivered by the group. “I can’t let you know the number of runs he that saved.”

Harrelson went 3 for 17 (.176) with three strolls when the Mets beat vigorously preferred Baltimore in the 1969 Worldwide championship. He had a .379 on-base rate during a seven-game misfortune to Oakland in the ’73 Series, after New York upset Cincinnati in the end of the season games.

“We don’t win in 1969 without him,” colleague Workmanship Shamsky said. “A warrior. The core of the group. He was a major piece of Mets history.”

As director of the Mets from 1990-91, Harrelson gathered a 145-129 record.

Derrel McKinley “Bud” Harrelson was brought into the world in Niles, California, on D-Day: June 6, 1944. He set off for college at San Francisco State and endorsed with the Mets in June 1963 for $13,500 despite the fact that the New York Yankees offered $3,000 more.

Harrelson said he was a little scared by the Yankees’ celebrated history and stressed he could stall out in the minors with them. He calculated the Mets, an extension establishment in 1962, could give a quicker way to the majors.

From the get-go in his expert vocation with the striving club, he attempted switch-hitting at Casey Stengel’s idea and stayed with it.

In 1972, Harrelson wrote an educational book named “How to Play Better Baseball.”

After his determination, Harrelson joined the governing body of Alzheimer’s Affiliation Long Island and worked with his family to bring issues to light. He actually made it out to Ducks games, enthusiastically welcoming fans as a generosity envoy regardless of whether he was unable to toss batting practice or mentor a respectable starting point any longer.

“I feel like I’m home when I’m there. I’m with my loved ones,” Harrelson told the Post.

“I believe individuals should realize you can live with (Alzheimer’s) and that a many individuals have it,” he said. “It very well may be more awful.”

In spite of his condition, Harrelson was at Citi Field in 2019 for the Mets’ 50th commemoration festivity of their 1969 title. Seaver, his old buddy and previous flat mate, didn’t go to after the Corridor of Notoriety pitcher was determined to have dementia.

In spite of his condition, Harrelson was at Citi Field in 2019 for the Mets’ 50th commemoration festivity of their 1969 title. Seaver, his old buddy and previous flat mate, didn’t go to after the Corridor of Notoriety pitcher was determined to have dementia.

“Mate was in excess of a colleague and father’s flat mate,” said Sarah Seaver, Tom’s girl, in a proclamation delivered by the Mets. “Father affectionately called him ‘Roomie’ until the end of their lives. What’s more, as far as I might be concerned, he was Uncle Bud, in every case speedy with a grin and a gleam in his expression. Father and Pal wanted to talk baseball together — however more than anything there was chuckling, gigantic grins and a great deal of affection between them.”

Harrelson is made due by his previous spouse, Kim Battaglia; little girls Kimberly Psarras, Alexandra Abbatiello and Kassandra Harrelson; children Timothy and Troy; 10 grandkids; and three extraordinary grandkids.

Leave a Reply