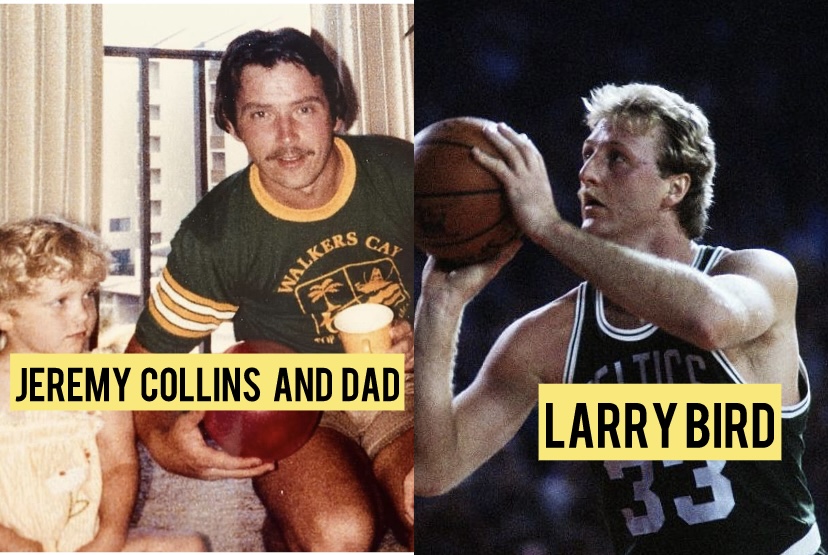

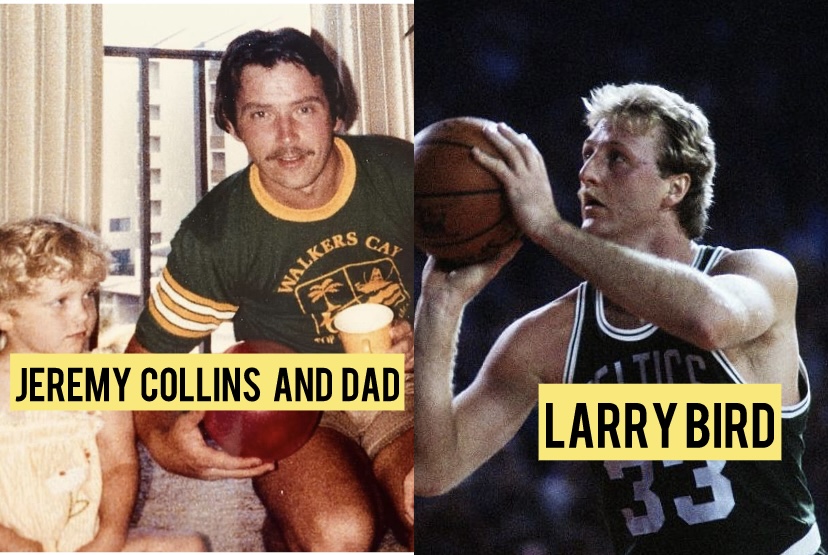

You first see Larry Bird’s jumper very close in December 1984 at the Omni pregame shootaround. Greater, blonder than on television, he depletes a large number of shots, many washes. You stress stealthily, age eight, and your dad scoops you up and sets you on his shoulders and folds his hands over your lower legs. Not all washes are equivalent. Some swush as though Bird has detected a dead center inside a dead center.

You live in Atlanta as Falcons fans, however your father grew up south of Bird in New Albany, Indiana. He’d prepared at different focuses to be a minister, legal counselor, and teacher, however rather than a gathering, court, or homeroom, he has you for a group of people. Together, you share Larry Bird. Every morning, he relates Bird’s case scores, and the digits turn through your school days. He labels stories of Bird with the hold back that Larry Bird was once a city worker, binding our authority record with this statement of belief. A divine being? Wash swush. A trash collector. With each shot Bird takes at the Omni, your father presses your tissue sufficiently to make an imprint.

You won’t ever draw nearer to Bird, the north star of your childhood, however he’s present in each discussion and stretch of quietness with your father. This is valid even on that December night in 1991 when your reality stops, veers off its pivot, and leaves you on a walkway seeing stars. He was unable to get you then, for there are places the kid should go where the dad can’t follow. Your father pointed past Bird to the incomplete venture of America. It was anything but an illustration you needed. It required vision. To see the entire floor. To review the game’s one time most noteworthy player, who hitched home following 24 days at Indiana College to function as a trash collector. You didn’t need an illustration. You needed to beat your father in one-on-one and he wouldn’t, for any reason or climate, yield.

The Faultless Gathering’s Extraordinary Truth

Inside the cool, fluorescent-lit room at the Interior Income Administration, columns of gigantic PCs produce numbers that will not make any sense for your dad. As a software engineer for the IRS throughout the mid year of 1991, somewhat recently of Larry Bird, your father brings his work and the numbers home. Your own number is fifty. Fifty free tosses. You both shoot fifty in sets of ten. Your father keeps count.

Bird shoots 100. Sets of twenty. His objective? 100 straight. At the point when he gets 99 in succession, he banks the final remaining one. “There were a few days,” Bird tells The Indy Star in 2015, “I was unable to miss. I could attempt to miss and wouldn’t.”

Notice – Read Beneath

At the line, your father sinks free toss after free toss and relates Bird at the line against the Trimmers, safe to the stunts of the San Diego Chicken. He subtleties the left-given jumper of New Albany’s Terry Morrison, who played AAU with Bird for Hancock Development. He then, at that point, inquires as to whether you understand what’s befalling Hoosier families at this moment. Unfortunate families like the Birds used to be. Ranch families in Stronghold Wayne? Working families in Gary? You don’t actually. You’re fourteen. “At this moment,” he expresses, “and across America, the rich crowd third homes and second yachts while steelworkers and plant laborers give blood to take care of their families.”

His words structure a foundation clamor, a music you attempt to block out. At the point when he advises you to twist your knees more profound and hold your completion longer, you tune in. Wash.

“35 for fifty,” he says.

His complete is 45. You quietly keep count and actually look at his work. He doesn’t cheat, your father. You have no real way to check his words on supply-side financial matters. A few evenings, you shoot alone until he flips on the floodlights and shows up with a major red cup. Diet Coke and Jack. He lectures on seaward assessment covers and the military-modern complex. Difficult to follow, such talk. You disdain the red cup, a shortcut for a recurrence you can’t get to. On those evenings, his shot is valid, yet his protection isn’t. You hate these games when he’s not at his best. You hate significantly more that he actually beats you.

So you post him up and place a shoulder in his chest. He gets short of breath simpler, sweats more. A bourbon sweat and Brut face ointment. A fragrance you’ll wear to bed. You armbar him. You don’t get his noble fierceness. You can’t see the foundation of his fury. You resent his knowledge, his ability to string together words, passages, and pages in the air. At the point when he shoots, you yell and entangle his arrival. Take that, you think. You don’t have any idea what you can’t help contradicting yet realize you need to. Without any words to match his, you siphon phony and go to the edge and you’re both airborne as your arms tangle and gravity guarantees its freedoms. His huge squeeze and boozy snicker dampen your fall.

“Foul,” he says.

You head to the highest point of the key, breathing hard.

“No foul,” you call.

He focuses to your busted lip.

“Sorry,” he says and movements for a break.

“Actually take a look at ball,” you say.

He gets the ball, moans, spills, and nails a foul shot. Getting the red cup, he heads inside.

Until the end of the mid year of ’91, you play more H-O-R-S-E. In the event that you excel, he changes to his left hand. Lefty free tosses. Left snares. Left-gave corner jumpers.

“Not fair,” you say, however it is fair and a relentless Larry Bird could never express such words.

“Is life?” your father counters.

You both gauge life’s general decency before the television on November 8, 1991. Falcons at Celtics. The camera focuses in on a pale Larry Bird. “Sorcery,” your father says.

Notice – Read Underneath

Wizardry Johnson reported a day sooner that he’d contracted HIV. Back in Lansing, Earvin also rode the dump truck with his dad before day break. Some keep thinking about whether Enchantment has days left, yet Bird checks passing’s entryway out.

“Perceive how he runs,” your father says. Bird’s step solidifies. “Look how he maintains a strategic distance from contact in the post. The jumper, his timing, is off,” he says. At halftime, the score is close. Your dad yawns.

“Larry ought to have been left last year,” he says and wishes you goodbye.

“Horse crap,” you say.

Your dad turns, and the air shifts. You’ve never reviled under his rooftop.

“Say once more?” he inquires.

You believe he should remain up regardless of whether it implies a talk. You need to talk Larry Bird.

“Ten bucks Bird plays the remainder of the time.”

He shakes his head.

“Ten says he makes second group All-NBA.”

“No, child.”

“Fine,” you say, “yet Bird will complete the year.”

“I trust you’re correct,” your dad says. “Goodbye.”

He’s the hardest player who at any point lived and they won’t ever be any other person close.

You’re fifteen. Fathers don’t tire. Wizardry won’t pass on. Bird can’t break. In the final part, Bird is a shadow. The Falcons win without any problem. “These have been the two hardest days since my dad died,” Bird says post-game. “I’ve been discouraged, and I’ve been out of it.”

Ad – Read Underneath

Bird completes 5-14.

“That was the initial time in my life I played in a game that I would have rather not played,” Bird tells Rick Reilly in 2012. “I had nothing that evening.”

“That was the initial time in my life I played in a game that I would have rather not played,” Bird tells Rick Reilly in 2012. “I had nothing that evening.”

In any case, Bird rallies — Lar-ree, Lar-ree! — as though woven into the loop universe is reality that Larry Bird won’t just ever quit being Larry Bird.

“27 against the Suns,” you report to your father.

“32 against Orlando and ten bounce back,” you add.

“31 against New York,” you messenger, “and twelve sheets.” Your father gestures.

The Knicks game is just before his birthday. Bird turns 35 — the eighth most established player in the NBA. “I didn’t think I’d at any point returned,” he says, “I thought it would have been my last game each game out.”

On the night he goes for 31 against the Knicks, Bird hits fourteen of fourteen free tosses. Wash swush.

Leave a Reply